By: Norm Miller, Hahn Chair of Real Estate Finance at the University of San Diego School of Business and affiliated with the Burnham-Moores Center for Real Estate.

Supporters of rent control suggest it is necessary in an era of unaffordable housing. Of course, if you are old enough and have followed the housing market, it seems that California has always been in an unaffordable housing crisis.[1] A recent report focused on Los Angeles suggested a “shortfall” of some 500,000 affordable housing units.[2] Many cities in California seem to be considering rent control at this time.[3] Long Beach, Inglewood, Glendale, Santa Ana, Pasadena and Los Angeles County are all considering joining a band of California cities that already have rent control and “just cause” eviction laws that prevent landlords from ousting tenants in good standing. There is even a statewide effort to put an initiative on California’s November ballot that would repeal the Costa-Hawkins Act, a 1995 law that severely limits rent control in the 17 California cities that already have it.[4]

The challenges of providing affordable housing are most pronounced in large coastal cities, where healthy economies have pushed housing from the demand side. At the same time, political activism (NIMBY’s for Not in My Back Yard), has spurred development challenges and hurdles, such as excessive parking requirements, maximum height limits and development fees that are not prorated by unit size, so that only larger unaffordable units are provided in the non-subsidized private portion of the market. Traffic and congestion are always cited as reasons not to permit any development dense enough to be mainstream market affordable. Some of these same activists will be found protesting all new developments, as they do not seem to realize that as long as they continue to have kids and expand the population base, the housing problem will only get worse unless more density is allowed. Rather than point fingers at ourselves as the primary cause of the problem, some naïve voters are now supporting more rent controls in California. Be careful what you wish for.

Proponent of rent controls argue that tenants can be exploited if building owners are allowed to raise rents to market levels and in some cases tenants will become homeless. Rent controls vary by market, but in most markets, rents can be increased only when a tenant moves out, so the landlord-tenant game becomes discovering when the real tenant moved out and the sub-let secret tenant moved in, often paying the original tenant a large windfall gain beyond the current rent. In some markets, only new or rehabilitated units can have rent increases, so the landlord-tenant game becomes one of waiting for the tenants to move out, then “rehabilitating” the unit to the minimum level necessary for a new market based rental charge. New York City is a classic case of such rent controls and a great laboratory to show what happens with long term rent controls.

While many of us understand the intension behind rent controls, few free market economists find any redeeming value in rent controls. Opponents to rent controls find such regulation is not only terribly inefficient, but also inequitable in serving a city’s residents with different levels of windfall gains extracted like a tax from landlords. Abuses are sometimes difficult to detect with rent-controlled units. Various “lucky,” long-time residents of rent controlled units receive more benefits than other newer residents or those residents living in areas without rent controls.

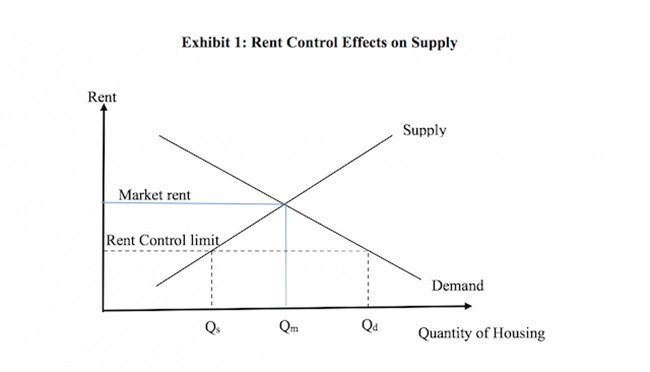

Rent controls hurt residents in the longer run in that such controls result in less housing investment (maintenance and repair) and less new stock than otherwise. With less housing stock, rent controls result in a rationing system where units subject to rent controls have huge pent up demand. The problem is illustrated in the graph, Exhibit 1 below. Over time as market rents exceed controlled rents, the demand at the controlled rent level is Qd while the actual supply is Qs rather than the market solution at Qm.

The gap between Qs and Qm is a shortfall in supply that the market refuses to provide at lower rent levels. In fact, over time, the gap continues to grow and the housing affordability problem, for those not in rent-controlled units, becomes even worse. That is, new rental housing is simply not built, except for subsidized development, where the profit comes from fees and rents do not matter. Developers would build units to sell as condominiums or even convert apartments to condominiums rather than be subject to rent controls, when possible.

Here is what we know will happen in the housing market, if extensive rent controls are enacted:

Fewer units will be built over time leading to an even greater housing shortfall.

Units subject to rent control will not be well maintained and owners will not provide amenities or services that are otherwise designed to keep tenants.

Landlords will discriminate more on tenant selection, seeking those more likely to move out versus those likely to stay long term.

Housing unit quality will deteriorate and tenants will need to maintain their own units.

Values will fall leading to possibly more defaults and foreclosures.

Value implications

How much will values fall? The greater the difference between the natural expected growth rate in rents and the rent-controlled rate, the larger will be the increase in cap rates. Currently, we can estimate cap rates based on the typical going-in net operating income over price. For multifamily in California, assume this is around five percent currently. The five percent cap rate is based upon an expectation of rental growth. If that rental growth rate is constrained so that two percent becomes more realistic rather than three and a half percent, the effect on the cap rate will be to drive it up by approximately one and a half percent to six and a half percent. When you divide any income level by six and a half percent instead of five percent, you lower the value by thirty percent. This means that an apartment building that was worth $1 million is now worth $700,000, assuming the rent controls are long term. The mortgage on the building, if fairly new, may be more than the $700,000 and some owners will simply hand over the keys to the bank. Others might milk the property and let them deteriorate. But few new multifamily property developers would enter such a rental market. They may provide more single family and condominium type housing to owners, who might rent them out if small owners are exempt from rent controls and this would result in a very fragmented, but still under-supplied market.[1]

Conclusions

Rent controls result in reducing future housing supply, providing a windfall gain to a few tenants while gutting the value of existing rental stock, and lowering the quality of rental housing over time. It would result in more residents needing to leave California rather than helping future renters stay here, thus hurting the businesses and economy that has so successfully supported a strong housing market to date. What will really solve the affordability problem for tenants are state enforced approvals of new housing developments with greater density, higher maximum heights, lower parking requirements, development fees prorated by unit size and some protection from politically motivated CEQA lawsuits that do nothing but delay projects and raise the costs of production.

References

1 For example, see Locked Out: California’s Affordable Housing Crisis, Erin Riches and Jean Ross, May 2000 at http://calbudgetcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/0005lockedout.pdf

2 See http://1p08d91kd0c03rlxhmhtydpr.wpengine.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Los-Angeles-County-2017.pdf SCANPH Southern California Association of Non Profit Housing, May 2017.

3 See for example “Rent control gains traction as housing costs ‘crush’ tenants” in the Orange County Register by Jeff Collins, March 24, 2018.

4 IBID quote from Jeff Collins.

5 For details on the value effects see Geltner Miller “Commercial Real Estate Analysis and Investment” On Course Pub, 3rd Ed. 2015.

Contact:

Kimberly Malasky

kmalasky@sandiego.edu

(619) 260-4786